IB Physics Topic 4 Notes

D1: Gravitational fields

Newton's law of gravitation

At this point in the syllabus, gravity has been mentioned as few times. In Topic A.2, it was mentioned that the gravitational force can be regarded as a centripetal force in some scenarios. In Topic D.1, you learn more about the gravitational force.

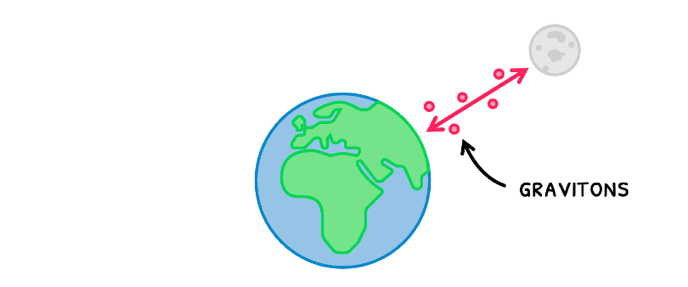

The gravitational force is governed by Newton's law of gravitation, which states that every mass in the universe attracts every other mass in the universe. This occurs because every mass releases gravitons that exert the gravitational force on other masses.

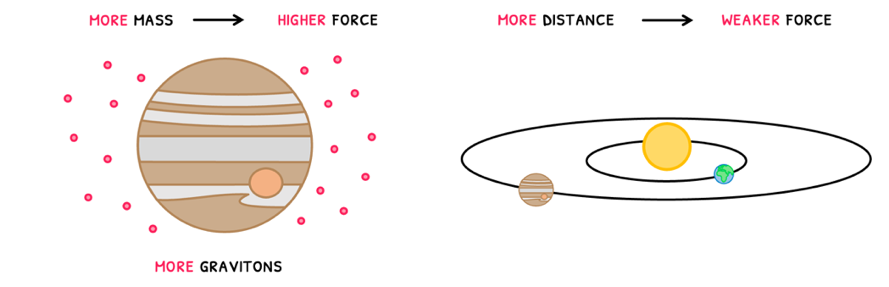

The more mass there is, the more gravitons are released and thus the higher the exerted gravitational force. However, the further away the other mass, the weaker the exerted gravitational force. If you remember, this is very similar to how the electrostatic force behaves.

The formula for gravitational force is given by:

F=Gr2m1m2

In this, G is the gravitational constant, equal to 6.67 x 10-11 Nm-2 kg-2.

Although the gravitational force is present between all objects, you likely know yourself that this is not felt unless the masses are huge. For such masses, let’s explore how we describe gravity via their gravitational fields.

Gravitational fields

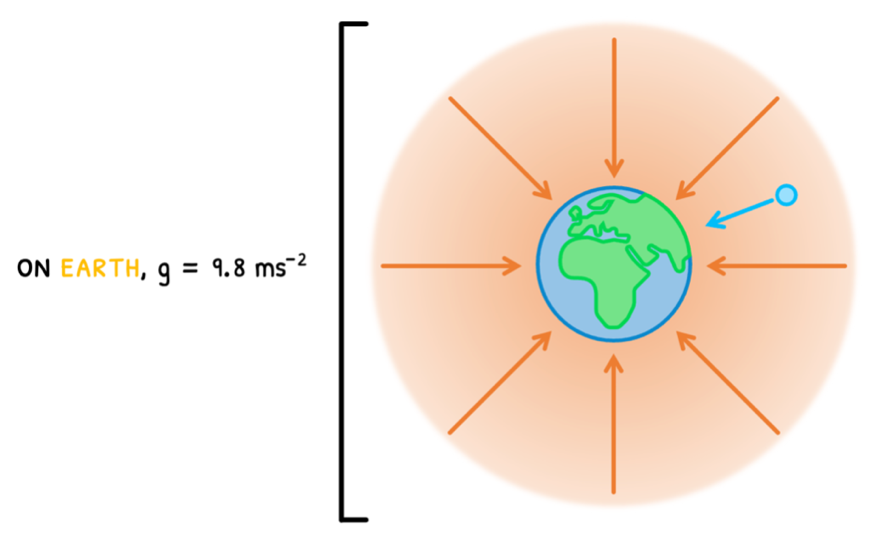

Like an electric field is the area wherein there is an electrostatic force per unit test point charge, a gravitational field is defined as the area wherein there is a gravitational force per unit test point mass.

The strength of this gravitational field (g) at any point is the force exerted per unit point mass, measured in N kg-1 or ms-2. On Earth, the gravitational field strength is 9.8 ms-2.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D1: Further gravitational fields (HL)

Gravitational potential

In Topic B.5, you learned that electric fields have a potential difference. The same applies to any other field, including gravitational fields. Thus, gravitational potential (Vg) is the energy per unit test point mass, measured in J kg-1. Newton’s law of universal gravitation provides a formula for the gravitational potential at a distance (r) from any point mass (M):

Vg=r−GM

Remember that when a test point is moved:

- Parallel to field lines - the test point mass is moving in the direction of the force. Therefore, work is done on the object.

- Perpendicular to field lines - the test point mass is not moving in the direction of the force. Therefore, no work is done on the object.

When work is done moving a test point mass between two locations, the energy is transferred into changing its potential. Therefore, there is a gravitational potential difference (ΔV) between the two locations. The gravitational potential difference (ΔVg) is defined as the work done moving a test point mass per unit test point mass, measured in J kg-1.

If work is done on the test point mass to change its potential, the potential difference will be positive. If the test point mass does work itself to change its potential, the potential difference will be negative. The formula for this is:

W=mΔVg

Whenever the potential difference is measured, it assumed that the gravitational field strength is constant and that the gravitational potential energy at the surface is zero.

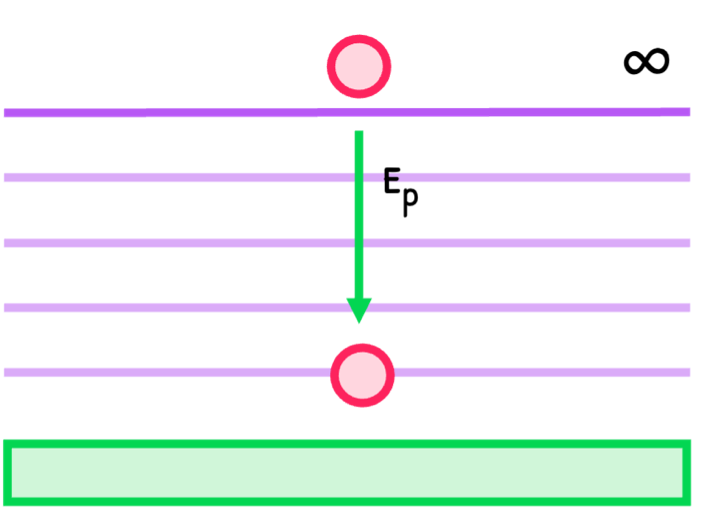

Since this is not the case, infinity is the point of reference considered the zero of gravitational potential energy. As such, gravitational potential energy (Ep) is defined as the work done in moving a mass from infinity to any point in space.

The formula for this is:

Ep=−rGMm

Equipotential

However, when no work is done in moving an object in a field, the locations must have no potential difference. These locations are said to be equipotential. Orbits are an example of an equipotential location.

Equipotential lines are represented as lines perpendicular to the field lines, since that is the plane of motion wherein no work is done moving a test point.

For example, if the field diagram is:

The equipotential diagram is:

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D2: Electromagnetic fields

Charge

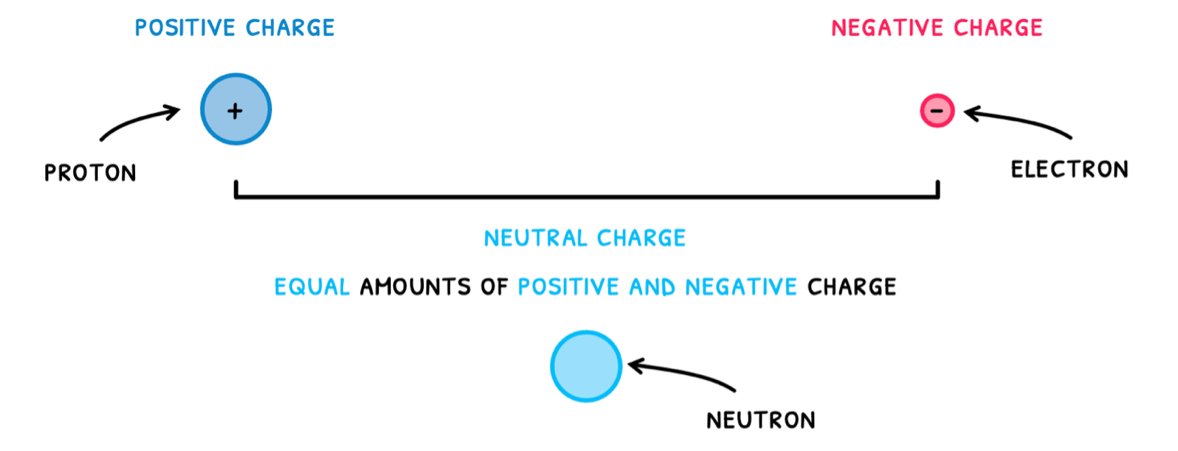

Topic D.2 focuses on the basics of electricity and magnetism. Since electricity is generated by the movement of charged particles, we need to understand what charge is. If you remember, there are two types of charge.

- Positive charge – found in protons

- Negative charge – found in electrons

Neutral charge, found in neutrons, is the presence of equal amounts of positive and negative charge.

Because protons and electrons compose all matter, charge is a fundamental property of all matter. The unit of charge is denoted by q and measured in Coulombs (C), where 1 C = the charge of 6.25 x 1018 particles.

Oil drop experiment

The oil drop experiment was performed by Millikan and Fletcher in 1909 to measure the charge of an electron and begin quantifying charge. This experiment was groundbreaking for quantum physics, eventually leading to a Nobel Prize for Millikan.

The experiment occurred as follows:

- A fine mist of oil droplets is sprayed into a chamber above two metal plates.

- Friction of the oil with the nozzle causes some of the oil droplets to become charged, but this can also be induced via X-ray.

- Oil droplets fall into the space between the two metal plates.

- When the field is turned on, charged droplets move to the plate they are attracted to.

- The oil droplets are observed through a microscope and the voltage is adjusted so only one oil droplet remains.

- When the electric field is turned off, the terminal velocity of the droplet is measured and used to calculate its radius and electric force (F) it experienced.

- The electric field is turned back on, and the charge of the droplet is calculated via the equation:

F=dqV

Performed over many oil droplets, Millikan was able to calculate the charge of an electron (e) to within a standard error of 2% at 1.5924 x 10-19 C. The value you are given in the IB data booklet of 1.60 x 10-19 C was agreed in 2014 and made slightly more precise in 2019, highlighting Millikan’s success at his time.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D2: Further electromagnetic fields (HL)

Electric potential

In Topic B.5, you learned that electric fields have a potential difference. You know need to learn about this in more detail. For this, we start electrical potential (Ve) is the energy per unit test point chrage, measured in J C-1. Just like gravitational potential, the electric potential at a distance (r) from any charge (Q) has the formula:

Ve=rkQ

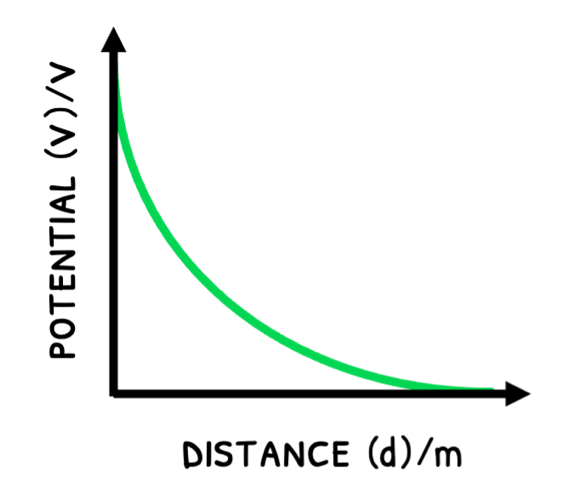

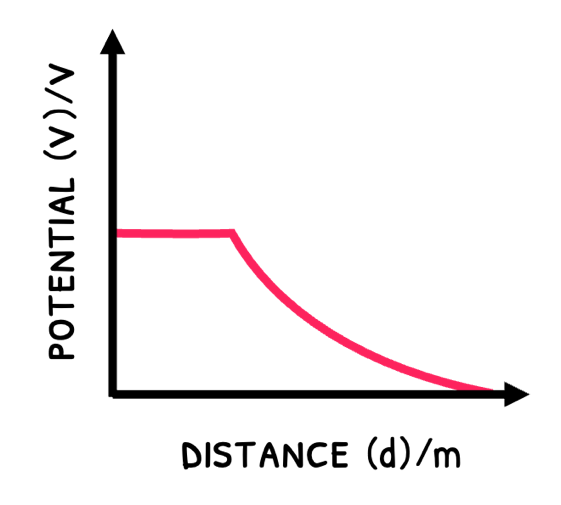

However, potential varies with distance from a point charge and spherical charge:

- In a point charge: potential exponentially decreases with increasing distance from the charge.

- In a spherical charge: charge is uniformly distributed so the potential is maximum until the surface. Beyond this, the potential exponentially decreases.

Remember that when a test point is moved:

- Parallel to field lines - the test point charge is moving in the direction of the force. Therefore, work is done on the object.

- Perpendicular to field lines - the test point charge is not moving in the direction of the force. Therefore, no work is done on the object.

When work is done moving a test point charge between two locations, the energy is transferred into changing its potential. Therefore, there is a electric potential difference (ΔV) between the two locations. The electric potential difference (ΔVe) is defined as the work done moving a test point charge per unit test point charge, measured in J C-1.

If work is done on the test point charge to change its potential, the potential difference will be positive. If the test point charge does work itself to change its potential, the potential difference will be negative. The formula for this is:

W=qΔVe

Equipotential

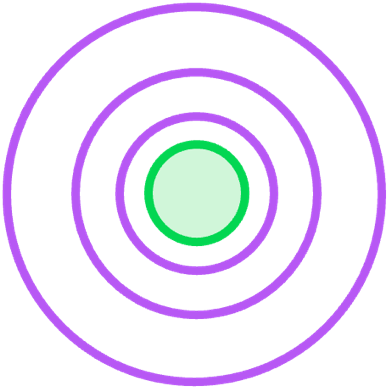

However, when no work is done in moving an object in a field, the locations must have no potential difference. These locations are said to be equipotential.

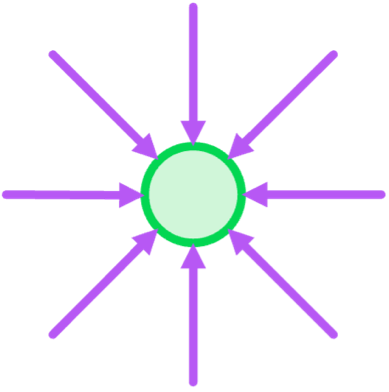

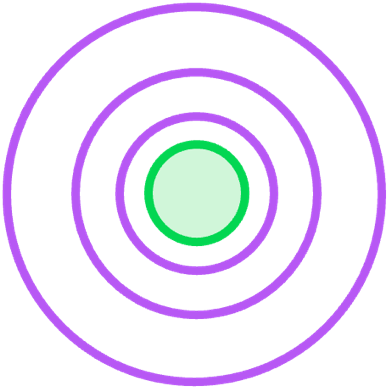

Equipotential lines are represented as lines perpendicular to the field lines, since that is the plane of motion wherein no work is done moving a test point.

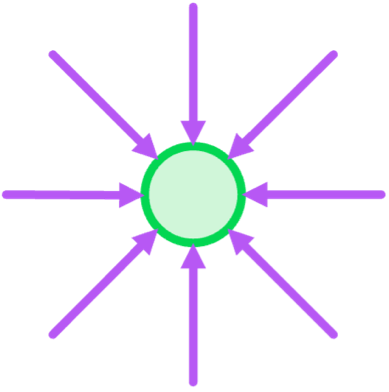

For example, if the field diagram is:

The equipotential diagram is:

Sail through the IB!

D3: Electromagnetic motion

The motor effect

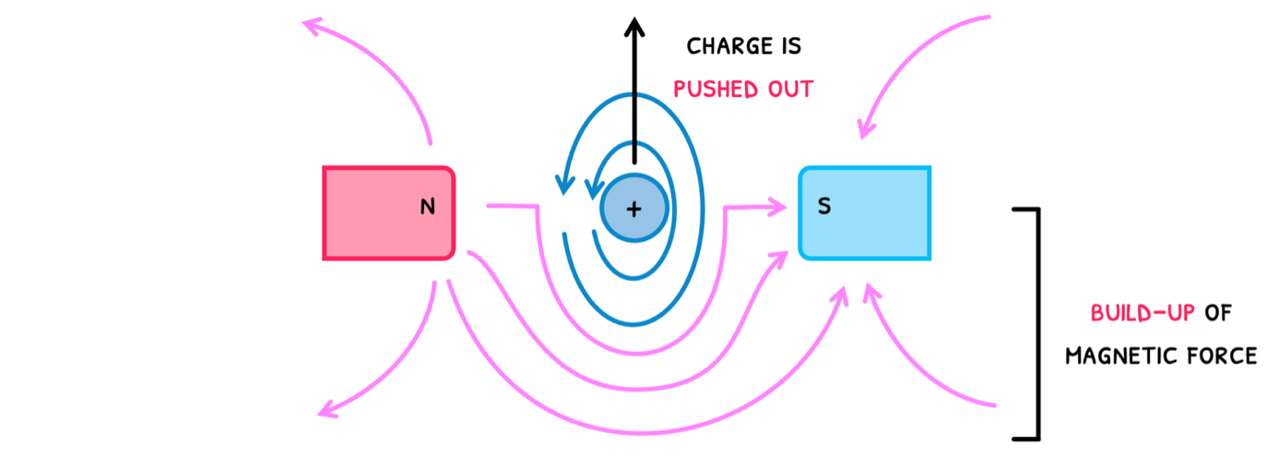

The last concept in Topic D you need to understand is what happens when charges travel through magnetic fields, meaning it crosses flux lines. This causes the charge's magnetic field and the external magnetic field to interact. Michael Faraday described a visual analogy to explain how this affects the moving charge:

- The external magnetic field basically conforms around the charge’s magnetic field.

- This creates a build-up of magnetic force around one side of the charge and an empty space on the other side.

- So, the built-up force pushes the only movable component of this system, the charge, out of the system.

This phenomenon is called the motor effect because it is applied to motors to convert electrical energy into kinetic energy.

You need to remember that if the magnetic field is stronger, or the charge has a higher value, velocity, or angle of crossing, the deflection is stronger. The formula for this is:

F=Bqvsinθ

Note that if a charge travels parallel to the external magnetic field, there is no interference of the magnetic fields and so there is no motor effect!

Now if the motor effect occurs with a single charge, it must also occur with multiple charges, ie a current! So, if a current-carrying wire crosses a magnetic field, it also undergoes the motor effect, just continuously. Understandably, the formula here changes:

F=BILsinθ

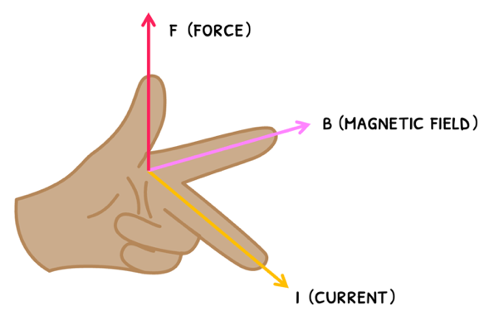

It can often be daunting to keep track of the directions of the forces and fields in these situations. If you ever forget them, use Fleming’s left-hand rule. For this:

- Point your thumb, first finger and middle finger perpendicular to one another as shown.

- We can then remember that finger guns are used by the FBI, where F, B and I represent the symbols for force, field and current respectively. Thus:

- F is the motor effect force direction shown by the thumb.

- B is the magnetic field direction shown by the pointer finger.

- I is the current or charge direction shown by the middle finger.

Sail through the IB!

D4: Induction (HL)

Electromotive force

Now that you know how electromagnetic fields function, you need to understand how they are manipulated to our advantage via a process called induction.

To start, remember that the electromotive force (emf or ε) is the total energy difference per unit charge, measured in volts (V). However, it can be induced in a conductor with no current when it crosses magnetic flux lines. There are two principal ways in which this can happen:

- Moving a conductor through a magnetic field.

- Rotating a conductor through a magnetic field.

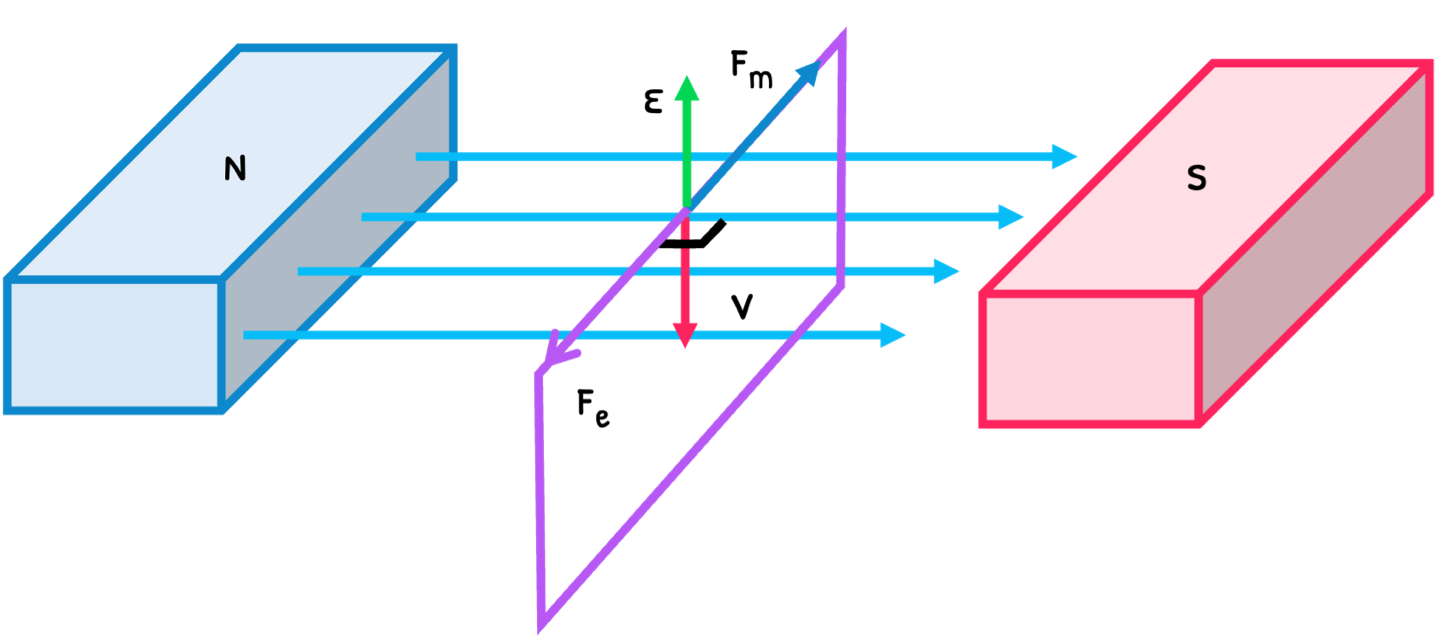

When moving part of a conductor through a magnetic field, the gain in magnetic potential energy induces a magnetic force (Fm) and electric force (Fe). Lenz’s law states that this induced magnetic field produces an electromotive force (ε) that opposes its original motion (v) through the magnetic field. This scenario is shown below:

The induced electromotive force is thus dependent on magnetic field strength (B), conductor speed (v) and length (L). The formula is thus:

ϵ=BLv

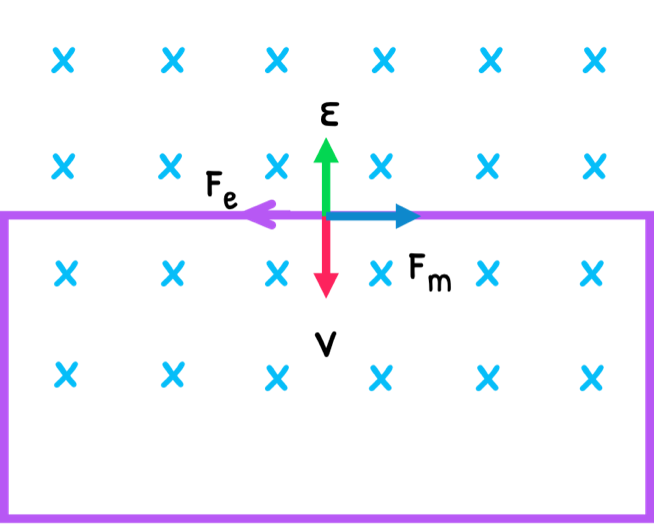

Flux

The magnetic field can also be drawn as a cross-section, with x’s representing flux lines into the page and dots representing flux lines out of the page. The same scenario is cross-section is shown below:

Since flux density is the equivalent of magnetic field strength, the formula for flux (Φ), measured in Webers (Wb) is:

ϕ=BA

If the area is at an angle to the field, the formula is:

ϕ=BAcosθ

Thus, an alternative definition of electromotive force is the rate of change of flux. Therefore, the formula can be rewritten as:

ϵ=ΔtΔϕ