IB Physics Topic 5 Notes

E1: Atomic structure

Evidence for atomic structure

Topic E focuses on nuclear physics. To fully understand this, you need to know the model of atomic structure. In early atomic modelling, three individuals were very important:

- Democritus considered the structure of matter, concluding that if one kept dividing matter, one would reach a particle that is indivisible, the atom.

- Dalton then took this one step further and decided that matter could be divided into different elements, which themselves were composed of atoms of different masses.

- Thomson fired electron beams at electromagnetic fields, determining the size and charge of an electron in the process. Using this knowledge, he developed the plum pudding model of the atom, which was composed of electrons in a matrix of positive matter.

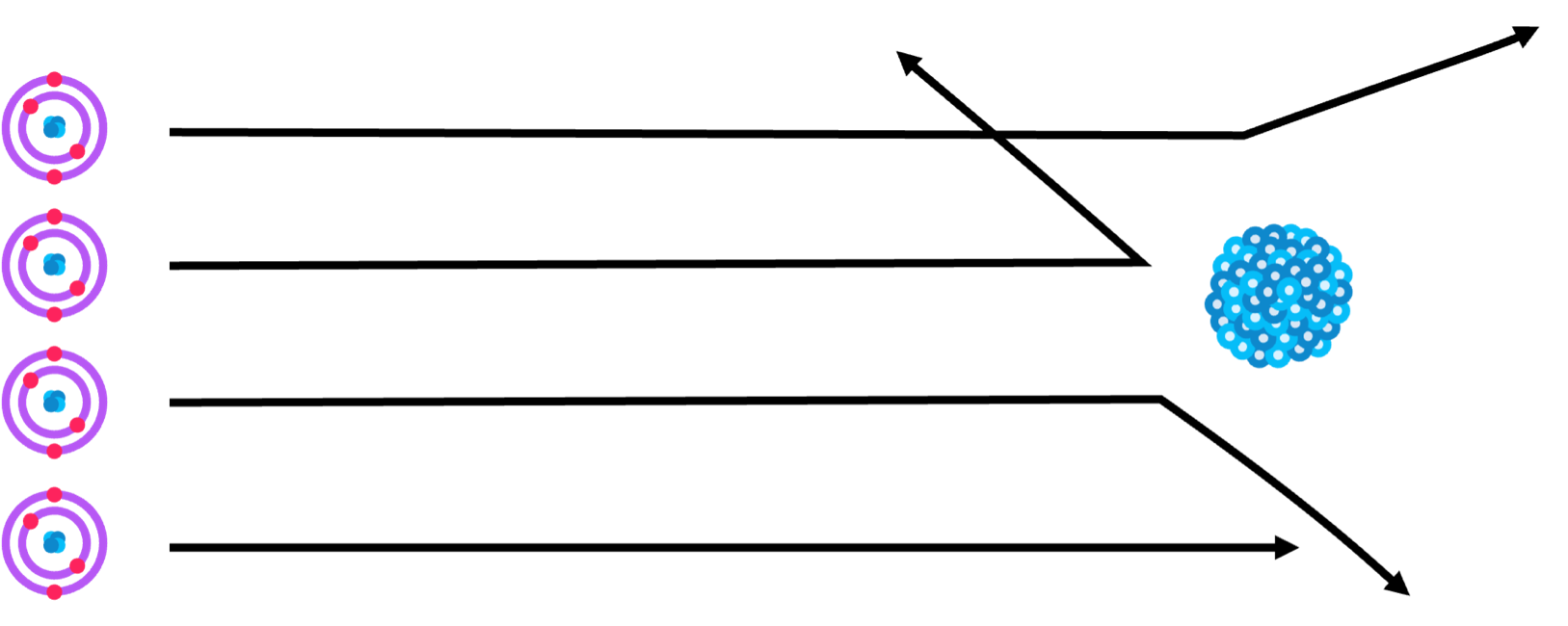

Following these early models, Rutherford uncovered the nucleus of an atom via the Rutherford-Geiger-Marsden experiment.

- In this, Helium nuclei were fired at a thin gold film to attempt to find structures.

- Some particles went straight through the film, but others were scattered at huge angles.

- The nuclei were already known to be positively charged, so the scattering suggested the presence of a strong positive charge in the gold film, the nucleus.

- However, the straight paths suggested there was empty space between the nuclei.

- This formed the basis of the Rutherford model: atoms consist of a positive nucleus surrounded by electrons in free space.

The Bohr model

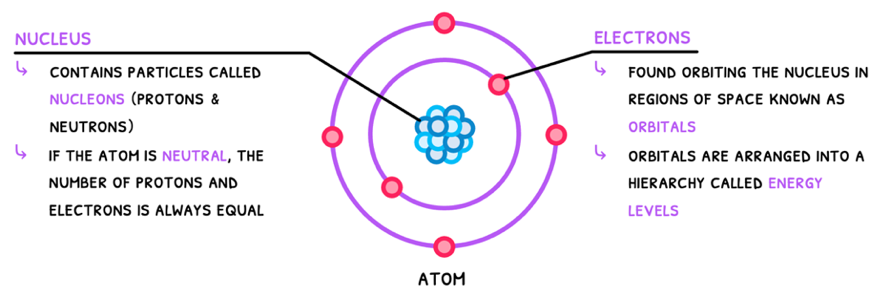

Finally, Niels Bohr discovered electron energy levels, using this to complete our basic model of the atom, known as the Bohr model. The IB requires you to know the Bohr model of the atom, which is composed of:

- A dense positively charged nucleus with protons and neutrons, termed nucleons.

- Negatively charged electrons in orbitals around the nucleus, arranged into energy levels/shells.

Each particle has a mass and charge, shown in the table below:

| Proton | Neutron | Electron | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (kg) | 1.673 x 10-27 | 1.675 x 10-27 | 9.110 x 10-31 |

| Charge | +1 | 0 | -1 |

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

E1: Further atomic structure (HL)

Nuclear radius

Remember that evidence for the nucleus was provided by the Rutherford-Geiger-Marsden experiment. During this, they found a clear relationship between a nucleus’s radius (R) and its atomic mass number (A). The equation is, where R0 is the Fermi radius, equal to 1.20 x 10-15 m:

R=R0A1/3

Additionally, at low energies, the intensity of α particles could be predicted from the angle of scattering, called Rutherford scattering. At high energies and low radii, however, this relationship disappeared.

So instead, nuclear scattering was performed with electrons. These do not feel the strong force and will instead diffract off nuclei. The wavelength of the fired electron can be calculated using the de Broglie formula:

λ=Ehc

Angular momentum

However, the Bohr model states that an electron does not emit energy when it is in a stable orbit. These are defined as orbits wherein the angular momentum (mevr) of the orbit is a multiple (n) of h/2π. The equation for this is:

mevr=2πnh

The energy of this orbit (En) is proportional to the inverse energy level2. The formula for this is:

En=−n213.6eV

E2: Quantum physics (HL)

The photoelectric effect

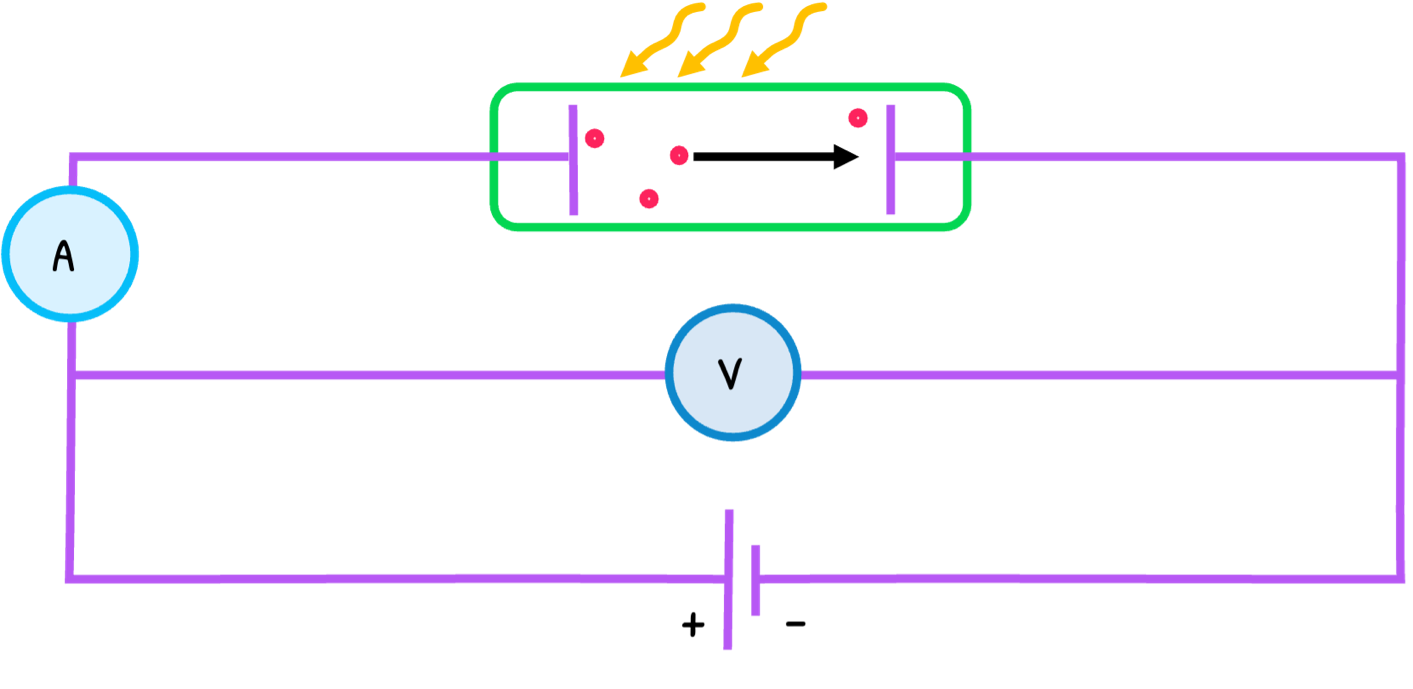

Electromagnetic radiation is traditionally thought of as a wave. However, Einstein proposed their nature to be particular in his explanation of the photoelectric effect, the emission of electrons from a metal surface when UV light shines on it.

The process is as follows:

- UV light with frequency f arrives in particles called photons. Their energy E is:

E=hf

- The minimum energy that electrons need to escape the energy is called the work function (Φ). Every electron absorbs a photon with a different frequency/energy and if the photon is below a threshold frequency (f0), no electron is emitted.

- If the energy is higher than the work function, the electron escapes and the remaining energy is converted into kinetic energy. The maximum kinetic energy (Emax) is:

Emax=hf−(Φ+ϵ)

- The number of electrons emitted depends on the UV light intensity.

- The process with a reverse supply is known as the stopping potential experiment. In this, the voltage is increased until electrons are decelerated to a point of no emission, called the stopping potential (Vs) and proportional to the electron’s maximum kinetic energy. The equation is:

Ek=Vse

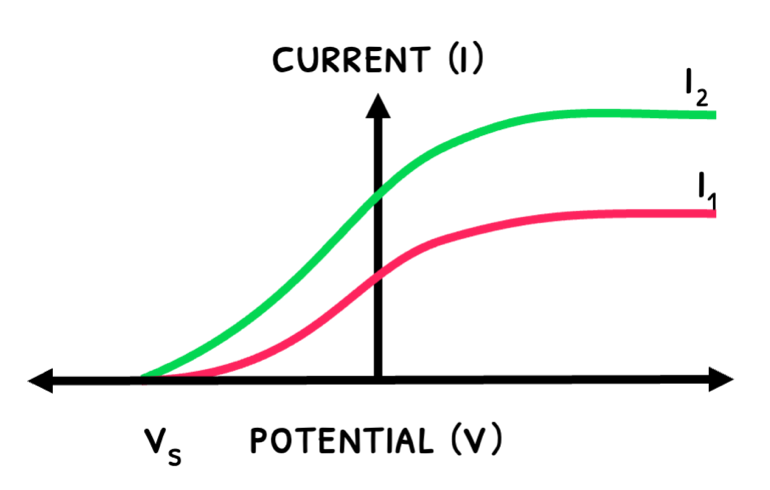

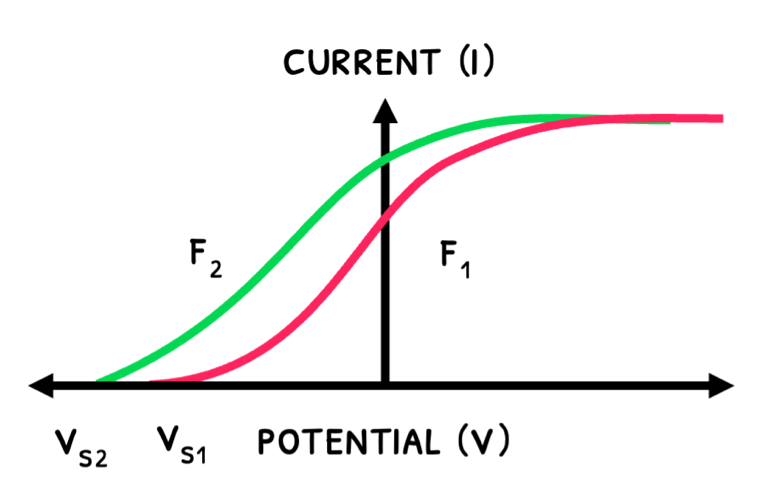

The graphs below show how the current varies with UV light’s intensity and frequency:

- An increase an intensity releases more electrons, increasing maximum current.

- An increase in frequency increases kinetic energy and stopping potential.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

E3: Radioactive decay

Nuclides

In Topic D.1, you learned about atomic notation. In this, it is important to understand that mass number and charge regularly change in chemical reactions, giving rise to isotopes and ions, respectively. These are collectively termed nuclides.

- Ions are nuclides that have lost or gained electrons, affecting their charge number

- Isotopes are nuclides with different numbers of neutrons, affecting their mass number. Understandably, this affects their stability.

Nuclear reactions

The number of neutrons in a nucleus ultimately determines the stability of the nucleus and whether it will participate in nuclear reactions. There are two types of nuclear reactions:

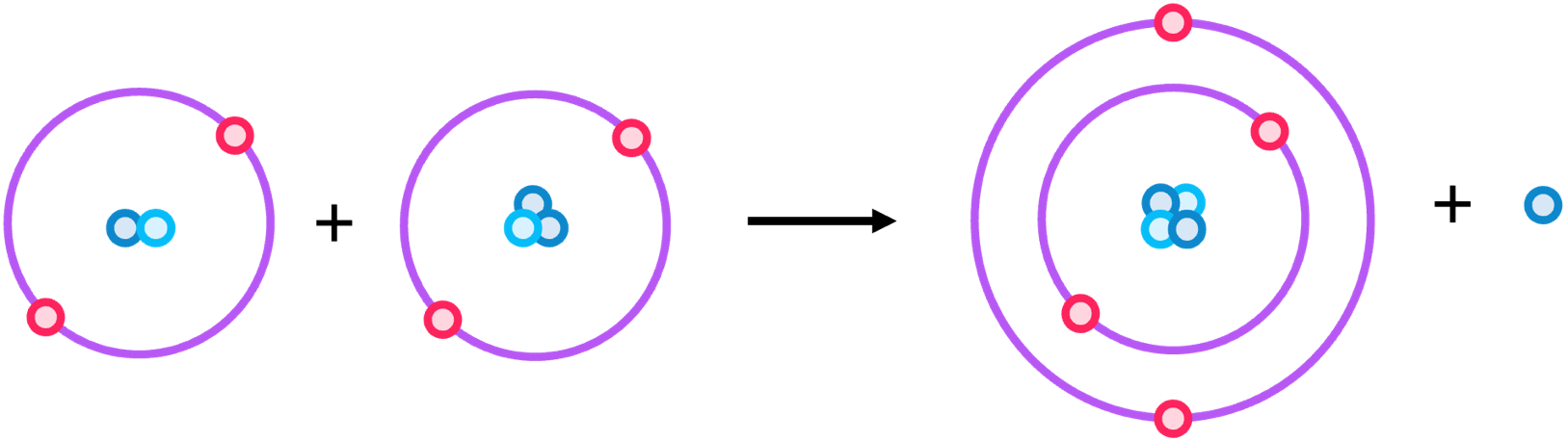

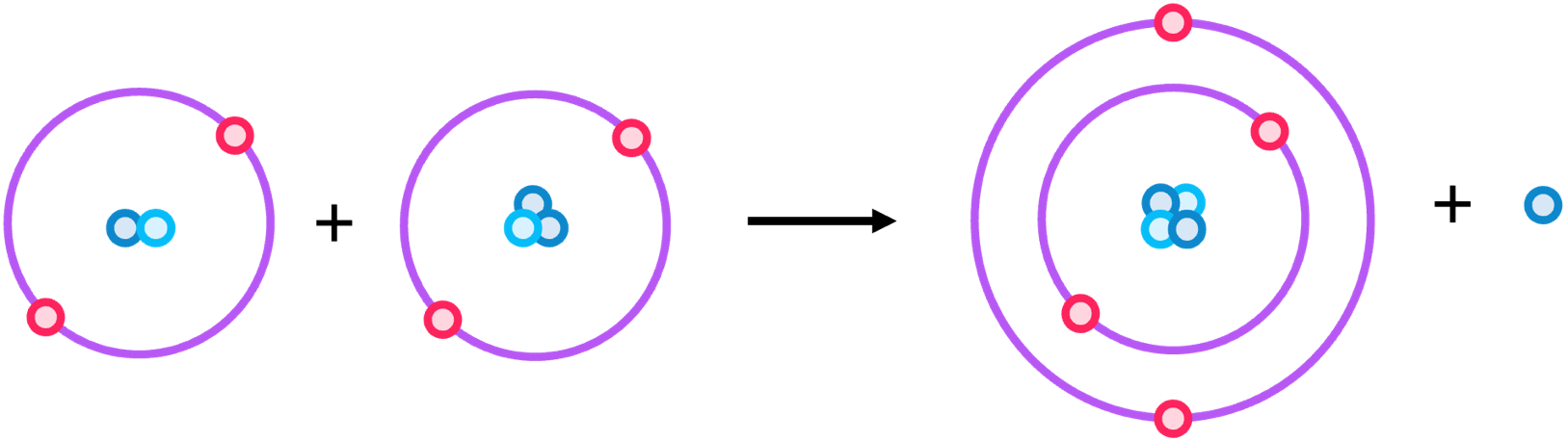

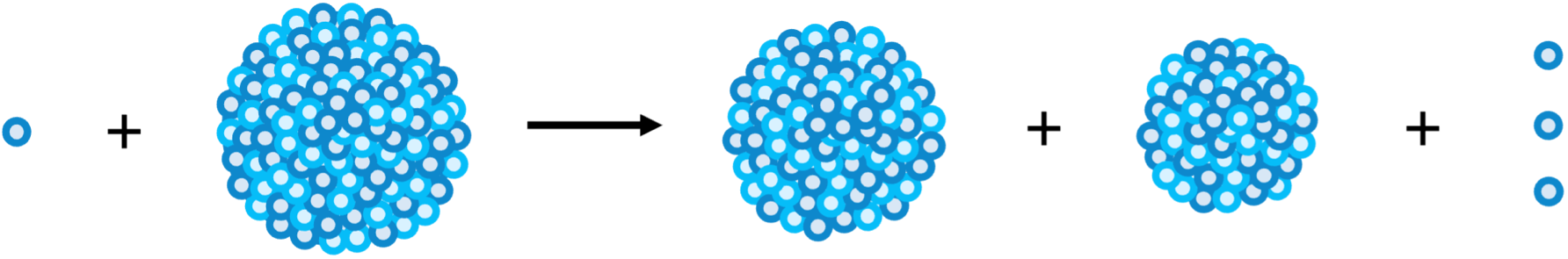

Fusion - the joining of two nuclei to form a larger nucleus, releasing lots of energy.

An example is the fusion of H-2 and H-3 to form He-4 and one neutron. This is the process that occurs in the sun.

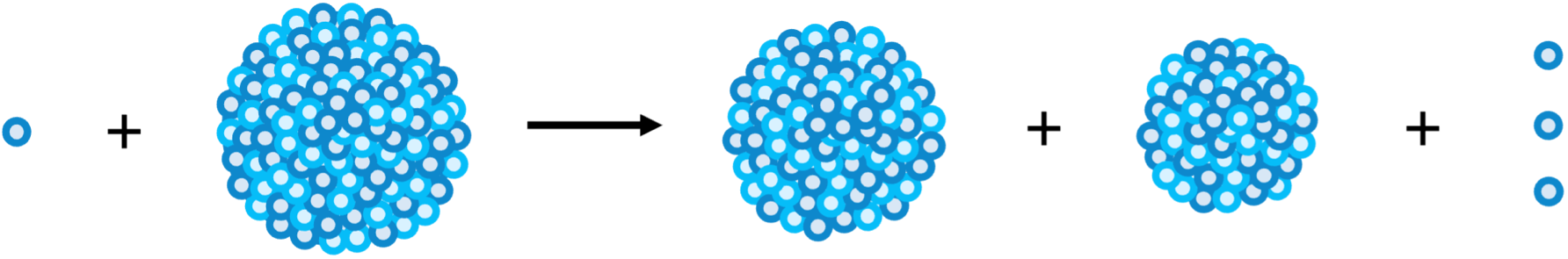

Fission - the splitting of a large nucleus into two smaller nuclei, releasing less energy, although still a large amount.

An example is the fission of a U-235 nucleus by a neutron into Ba-141, Kr-92 and 3 neutrons. This is the process that occurs in nuclear reactors.

Mass-energy equivalence

How the fission or fusion reaction produces energy is dictated by mass-energy equivalence. Mass-energy equivalence is a concept proposed by Einstein, which proposes that mass and energy are one and the same. This means if an object’s mass changes, its energy also changes. Mass and energy are related by the famous formula:

ΔE=Δmc2

So, just like energy is released when bonds form between atoms, mass is converted to energy and released when bonds form between nucleons. As a result, the mass of a nucleus is lower than the sum of the masses of the nucleons.

This is called the mass defect, defined as the difference in mass of a nucleus and the sum of its constituents. A consequence of mass equivalence is that atomic particle masses can also now be expressed in terms of their energy value.

In order to calculate this, we start by revisiting the masses of nuclear particles. All nuclear masses are based off Carbon-12, which has 6 protons and 6 neutrons and weighs 12.00 g mol-1. Since writing proton and neutron masses out every time is tedious, their masses were redefined to be simpler to work with, the unified atomic mass unit (amu). Here, 1 amu = 1/12th the mass of a Carbon-12 nucleus (1.661 x 10-27 kg). Then, 1 amu is associated with 1 u of energy = 931.5 MeV c-2.

The table from Topic 7.1 can thus be updated to show these two added units:

| Proton | Neutron | Electron | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (kg) | 1.673 x 10-27 | 1.675 x 10-27 | 9.110 x 10-31 |

| Mass (amu) | 1.0073 | 1.0087 | 0.000549 |

| Energy (u) | 938 | 940 | 0.511 |

| Charge | +1 | 0 | -1 |

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

E3: Further radioactive decay (HL)

Strong nuclear force

Remember that the strong nuclear force is essential to the existence of nuclei, as it overpowers the charge repulsion of protons to bind them together into one cohesive mass with neutrons. However, it is only tangible up to 2.0 fm, and its effect rapidly drops off after this. Like the other fundamental forces, you are expected to know the evidence behind this force. There are two fundamental pieces of evidence you need to be aware of:

- Nuclear binding energy – just as intermolecular forces, the creation of bonds releases energy whereas the breaking of bonds requires energy. The mass defect of nuclei is explained by the nuclear binding energy, which can only be caused by a bond between nucleons – the strong nuclear force.

- Rutherford scattering formula – this determines the scattered intensity due to electrostatic repulsion based on the energy of the fired alpha particles. However, high energy alpha particles deviate from this formula as they close in on the nucleus and are affected by the strong nuclear force, significantly decreasing the scattering intensity.

Nuclear stability

Whilst the strong nuclear force is powerful, as the number of protons in a nucleus increases (with increasing atomic number), the electrostatic repulsion between the protons also significantly increases. Neutrons are there to facilitate the strong nuclear force whilst spacing out protons to overall reducing the strength of the electrostatic repulsion and keep the nucleus together.

The stability of a nucleus has been tried to be explained by a constant ratio of neutrons-to-protons (N/Z ratio), but for stable nuclei of an increasing size, the neutron-proton ratio increases too. This is because:

- As nuclear size increases, more protons come into close proximity with one another.

- The built-up electrostatic repulsion outweighs the strong nuclear force if the ratio is 1:1.

- Thus, proton density must decrease as nuclear size increases to maintain stability.

- This results in an increase in the neutron-proton ratio.

Nuclear energy levels

The concept of nuclear stability suggests that nuclei possess specific energy levels. When viewing the nuclear binding energy curve, a few things are observable:

- From mass numbers 1 to 30, there is a great increase in nuclear binding energy per nucleon. This is due to increased forces per nucleon, causing a more tightly bound nucleus and releasing more energy.

- From mass numbers 30 to 60, the nuclear binding energy per nucleon decreases vastly as the forces per nucleon increase minorly.

- From mass 60 onwards, the binding curve is approximately stable. This is because the nucleus is now so large that nuclear force don’t extend across the whole radius, meaning that the electrostatic forces and strong nuclear force cancel out with each new nucleon.

- At the tail end of the curve, the heavier elements have a gradual decrease in binding energy per nucleon. This is because the nucleus is now so large that the strong nuclear force is not substantial enough to keep the nucleus together and so electrostatic repulsion begins to dominate more.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

E4: Fission

Fission

Now that you have learned the basics of atoms and radiation, you need to understand how energy is produced in nuclear reactors. There are two types of nuclear reactions:

Fusion - the joining of two nuclei to form a larger nucleus, releasing lots of energy.

An example is the fusion of H-2 and H-3 to form He-4 and one neutron. This is the process that occurs in the sun.

Fission - the splitting of a large nucleus into two smaller nuclei, releasing less energy, although still a large amount.

An example is the fission of a U-235 nucleus by a neutron into Ba-141, Kr-92 and 3 neutrons. This is the process that occurs in nuclear reactors.

Whilst fusion has a higher energy output, it currently requires a higher energy input to initiate and is thus not industrially viable for now. Thus, fission is the current reaction used in nuclear reactors.

Chain reaction

In a reactor, fission can be initiated one of two ways:

- Spontaneously - radioactive elements like Uranium are already unstable and will undergo radioactive decay by themselves without any external energy input. However, this occurs at low baseline levels and yields little energy.

- Neutron-induced - a neutron is fired at Uranium nucleus, colliding and making it more unstable. This instantly induces fission .

Following the initiation of fission reactions, remember that a Uranium nucleus will release three neutrons. At sufficient speeds, these can set off the fission of three other nuclei, with each setting off another three etc, called a chain reaction.

Due to the exponential growth of fission in a chain reaction, harnessing fission power is incredibly dangerous and needs to be well-monitored and controlled.

Sail through the IB!

E5: Fusion & stars

Fusion

Whilst fission is an important source of energy production in the world, due to its significant disadvantages there is much research focusing on fusion instead. This is a process that naturally occurs in the core of stars, causing their large energy emissions. The reaction that stars undergo is:

411H→24He+210e++2ν

As part of fusion, mass is lost to produce energy at a high rate, about 4 x 109 kg s-1 in the Sun. Eventually, this energy makes its way through the different layers of the star out to the surface. Here, the outward radiation generates massive amounts of energy every second to shine.

One of the important components to understand is how stars remain stable despite their high radiation output from the core. This is due the hydrostatic equilibrium generated by the gases:

- The radiation generated by fusion in the gaseous core produces a massive outward radiation pressure on the surface to push gases to the surface.

- On the other hand, the high density of gases in the star generate an equally massive inward gravitational force that pulls the gases inward.

- As a result, the outward pressure and inward pull balance each other out to form a fluid equilibrium, called hydrostatic equilibrium.

Star formation

However, you are expected to understand how a star develops to reach this point of hydrostatic equilibrium. The process occurs as follows:

- Star formation begins with large interstellar clouds composed of Hydrogen, Helium, and other materials.

- In these, the cloud’s temperature influences particular kinetic energy and expansion of the cloud while its density influences gravitational potential energy. Overall, if the gravitational potential is greater than the kinetic energy, the cloud remains bound together in equilibrium.

- These clouds can exist in equilibrium for years until an external event causes a change in the cloud’s mass.

- If the cloud reaches a mass greater than the critical mass (MJ) as according to the Jeans criterion, it starts to collapse. Typically, high cloud density and low cloud temperature are associated with a higher likelihood of collapse.

- Collapse of the cloud increases the kinetic energy and temperature of the particles, forming a proto-star.

- If the temperature is sufficient to trigger nucleosynthesis, the process is called ignition.

- The fusion reactions in the core slowly start to produce as much energy as is being radiated, maintain the temperature.

- At this point, hydrostatic equilibrium is established, forming the beginnings of a stable main sequence star.