IB Physics Topic 3 Notes

C1: Simple harmonics

Oscillations

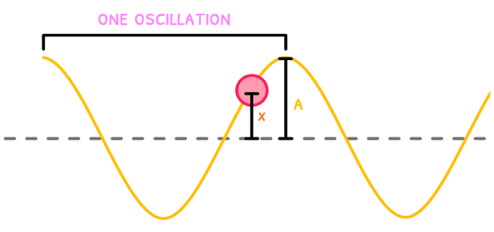

A core concept in IB physics is that of oscillations: which are the continual movement of an object around a fixed point, called its equilibrium position. You are expected to know five more properties of oscillations: displacement, amplitude, wavelength, period, and frequency.

- The displacement of the object (x) is the distance of the particle from its equilibrium position, measured in meters

- The amplitude of the oscillation (a) is the maximum or minimum displacement of the particle, also measured in meters

- The length of one oscillation is visible from crest to crest, or trough to trough, and can be defined by three terms: wavelength, period, frequency, and angular frequency:

- Wavelength (λ) is defined as the length of one oscillation, measured in meters

- Period (T) is defined as the time it takes to complete one oscillation, measured in seconds

- Frequency (f) is defined as the number of oscillations that occur in one second, measured in Hertz (Hz)

- Angular frequency (ω) is defined as the angular displacement of an oscillation in one second, measured in radians per second

Since angulary frequency, frequency, and period both measure oscillations in terms of time, they are related. The formula for this is:

T=f1=ω2π

Now that you know the properties of oscillations, we can discuss the two different types:

- Periodic - waves with a constant frequency and period.

- Aperiodic - waves with multiple frequencies or periods.

Path and phase difference

The IB expects you to be able to predict what happens when waves interact. For this to be possible, you are only expected to consider periodic waves of the same frequency.

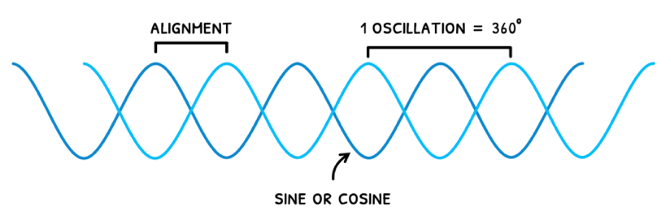

How they subsequently interact is dependent on their alignment, termed the the path difference (p) or phase difference (ø). These mean the same thing but have different units. This comparison is possible because the waves look like sine or cosine functions. Since they will have the same frequency, you can compare where the crests of one wave are relative to the other wave:

- The path difference is measured in number of wavelengths. Being ahead or behind one wavelength means the path difference is 1λ.

- The phase difference is measured in degrees or radians. Being ahead or behind one wavelength means the phase difference is 360° or 2π.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C1: Further simple harmonics (HL)

Formulae of simple harmonic motion

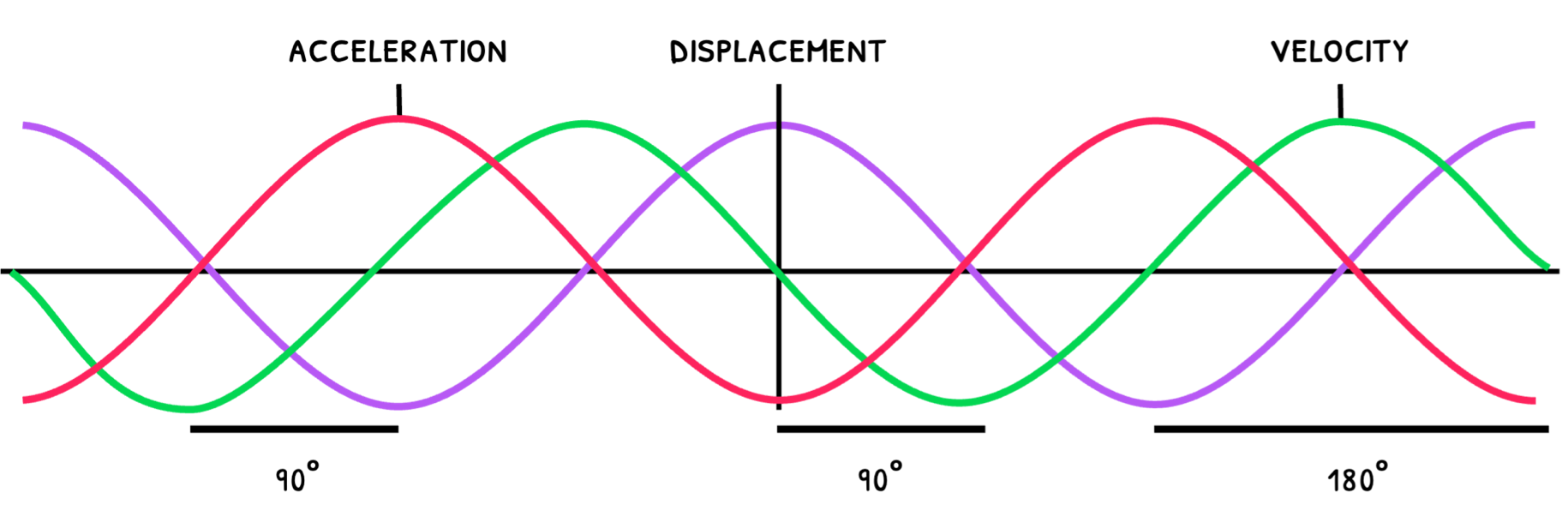

In Topic C.1 HL, you need to be able to quantify the displacement, velocity, and acceleration and the energies. To fully understand how this occurs, let's first review how these are related. Remember that the phase difference between displacement and velocity is 90°, velocity and acceleration is 90°, and displacement and acceleration is 180° as shown below:

Since simple harmonic motion is sinusoidal motion, an alternative way to describe the displacement, velocity, and acceleration is via trigonometric functions. The basic format of these is:

- a sin bx

- a cos bx

Here, a is amplitude and b is the period coefficient, whose corresponding values are shown below:

| Amplitude (a) | Period coefficient (b) | |

|---|---|---|

| Displacement (x) | maximum displacement (x0) | angular frequency (ω) |

| Velocity (v) | maximum velocity (v0) = ωx0 | angular frequency (ω) |

| Acceleration (a) | maximum acceleration (a0) = ω2 x0 | angular frequency (ω) |

Substituting in these values, the formulae we get are:

No displacement at t = 0 | Positive displacement at t = 0 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement (x) | x=x0sinωt | x=x0cosωt | |

| Velocity (v) | v=−ωx0cosωt | v=−ωx0sinωt | |

| Acceleration (a) | a=−ω2x0sinωt | a=−ω2x0cosωt | |

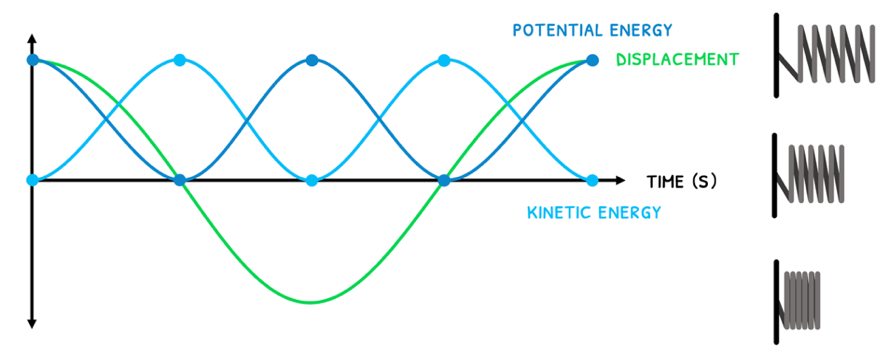

Also remember that kinetic and potential energy are continually transferred during simple harmonic motion to conserve the total energy, as shown below:

The key formulas are:

- Kinetic energy Ek=21mω2(x0−x2)

- Potential energy Ep=21mω2x2

- Total energy Et=21mω2x0

As such, the key relationships are that at:

- Maximum displacement - maximum potential energy and zero kinetic energy. Therefore, total energy is equal to potential energy.

- Zero displacement - maximum kinetic energy and zero potential energy. Therefore, total energy is equal to kinetic energy

- Minimum displacement - maximum potential energy and zero kinetic energy. Therefore, total energy is equal to potential energy

C2: Wave models

Travelling waves

In Topic C.1, you learned about simple harmonic motion. Remember that waves are one of the examples of oscillations that exhibit SHM. In this topic, you learned about a particular type of wave that does this, called a travelling wave.

A travelling wave is defined as an oscillating wave that transfers energy through a medium via the movement of particles in the direction of the wave. These waves always have a constant speed (v) that is dependent on wave frequency (f) or period (T) and wavelength (λ)

v=fλ=Tλ

However, particles can move in two directions, forming either transverse waves or longitudinal waves. Let’s cover each one now.

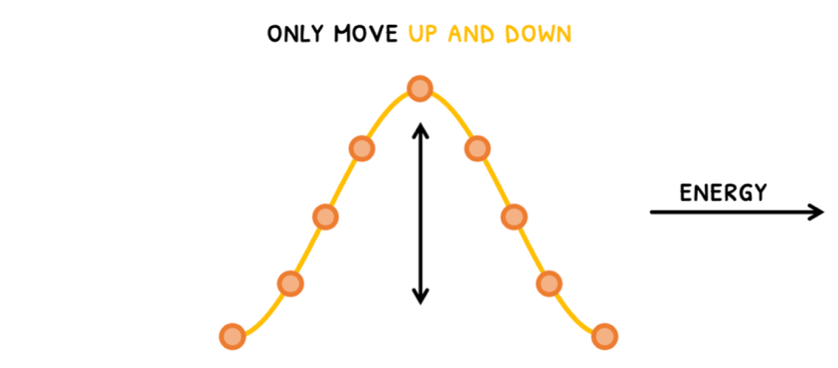

Transverse waves

In transverse waves, the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of energy transfer. Thus, if the energy is moving left to right, the particles only move up and down.

In these, the particles only move up and down from their mean position to create the wave shape. However, the energy travels perpendicular to this, in the direction of the wave.

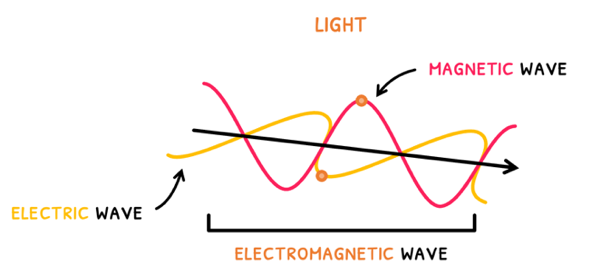

Common examples include water waves and light. However, light is special because it is composed of two transverse waves: an electric wave and a magnetic wave, collectively termed an electromagnetic wave.

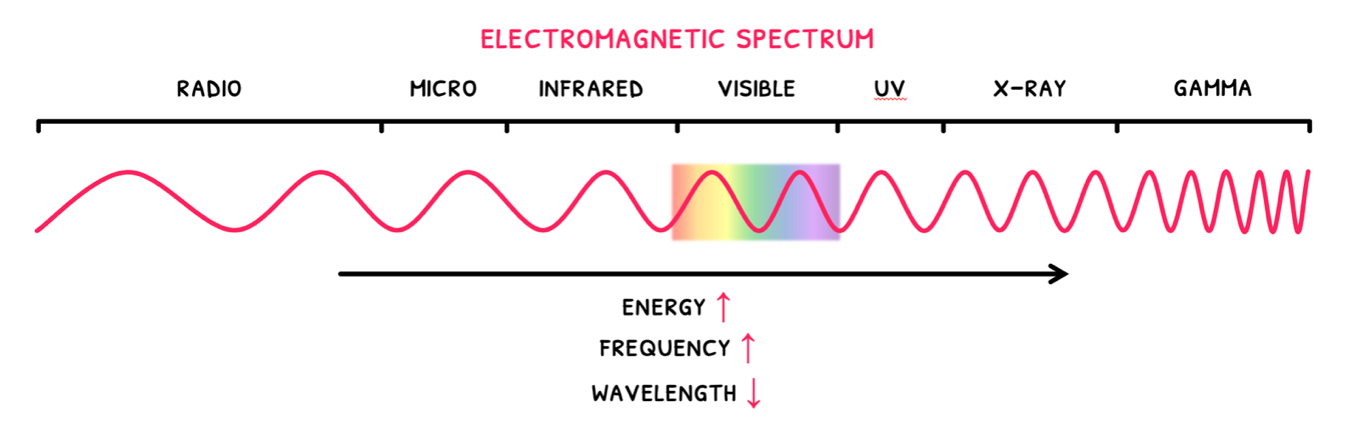

Electromagnetic wave are also known as electromagnetic radiation, which are a form of energy that travel as a wave. Whilst all electromagnetic radiation has a speed of 3 x 108 ms-1, wavelength (λ), and frequency (f) change to give different wave types and energies. These are all described by the electromagnetic spectrum.

The different types are radio waves, microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet light, X-rays, and gamma radiation. These can be remembered using the mnemonic Red Martians Invaded Venus Using X-ray Guns.

Additionally, it in this spectrum, it is important to notice that as you progress from radio waves to gamma rays:

- As wavelength decreases, frequency increases.

- As wavelength decreases, energy increases.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C3: Wave phenomena

Wave diagrams

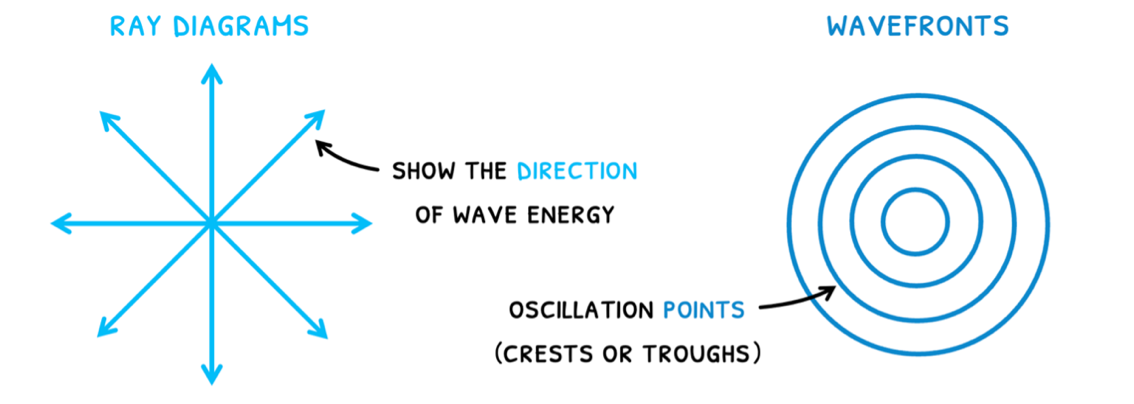

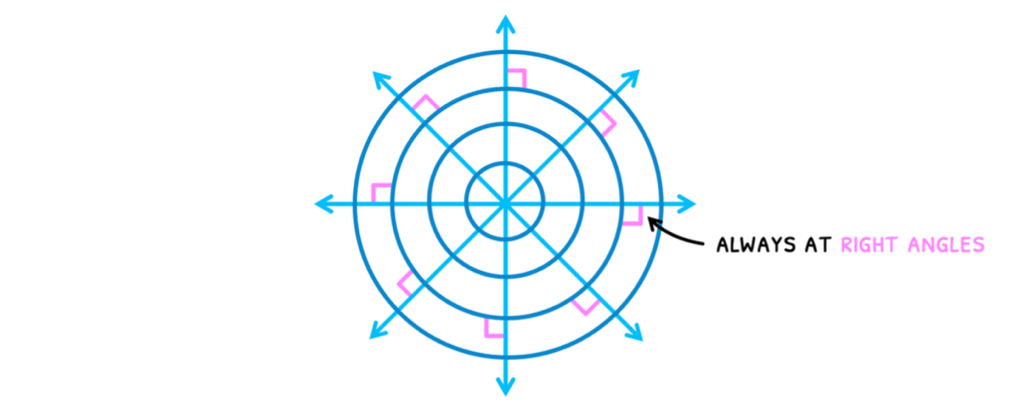

In Topics C.1 and C.2, you learned about oscillations, simple harmonic motion, and the types and properties of waves. In this topic, you cover the behavior of wavefronts. To understand this visually, this first starts by understanding how to visually represent waves. This can be done one of two ways:

- Ray diagrams – here, arrows show the direction in which the wave energy travels.

- Wavefront diagram – here, circles show the oscillation points of waves moving together i.e. crests or troughs.

Often these are combined into one diagram, as shown below. However, note that rays and wavefronts are always at right angles to one another.

Wavefront behavior

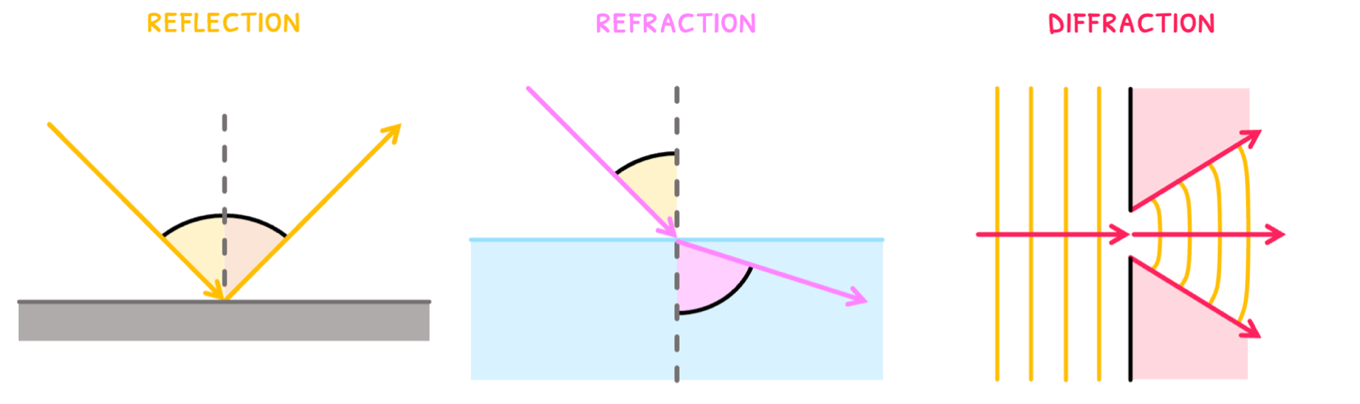

Now knowing how to draw waves, we can discuss how these waves interact with matter. Its interaction can be one of three types: reflection, refraction, or diffraction.

The way in which these occur, however, depends on the type of wave:

- In most waves, energy is transferred through large particles. As a result, the energy absorption properties of surface particles determine the observed interaction.

- However, in electromagnetic waves, energy is transferred through electrons. Each electron oscillates in place and re-emits a secondary wave. As a result, the interference patterns of these emitted waves determines the observed interaction.

Reflection

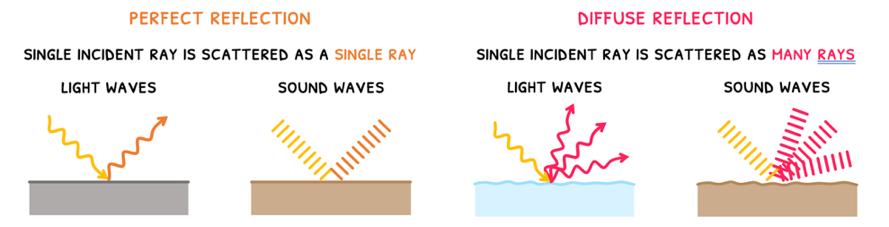

Let's start reviewing the phenomenon of reflection. This is defined as the scattering of a wave when it hits the surface of a medium. This can occur in two ways:

- Perfect reflection is when a single incident ray is scattered as a single ray.

- For light waves, this typically occurs with smooth metallic surfaces. This is because free electrons in the metal re-emit waves that destructively interfere with the incident wave and produce a reflection.

- For sound waves, this typically occurs with smooth hard surfaces. This is because their particles cannot absorb the energy and vibrate well, instead reflecting it.

- Diffuse reflection is when a single incident ray is scattered as many rays.

- For light waves, this typically occurs with rough non-metallic surfaces. This is because non-metals have internal structural irregularities that cause multiple reflections, and rough surfaces have external irregularities that cause multiple reflections.

- For sound waves, this typically occurs with rough hard surfaces. This is because hard materials reflect sound and rough surfaces reflect in multiple directions, both previously discussed.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C3: Further wave phenomena (HL)

Single slit diffraction

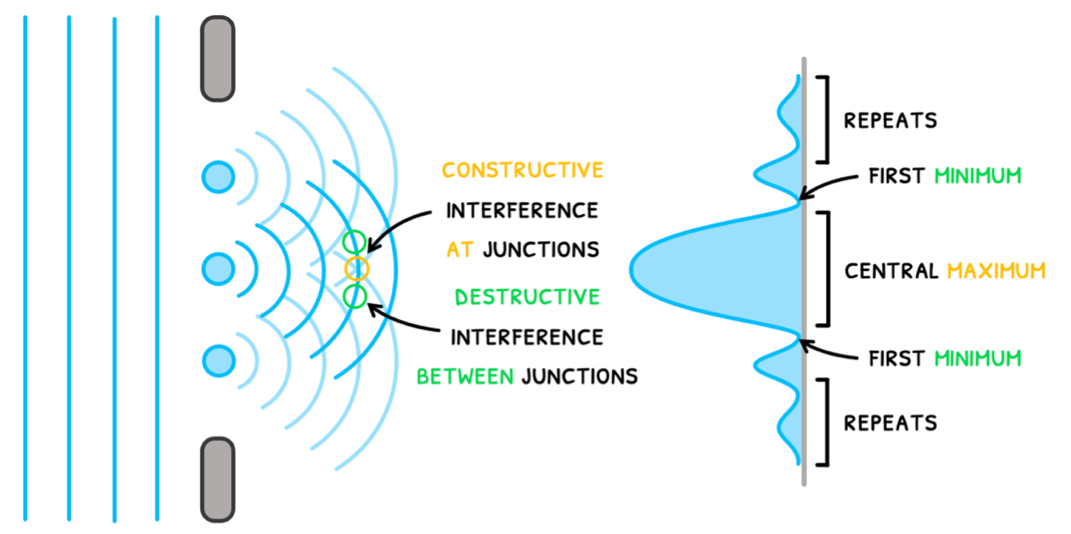

Remember that diffraction is the spreading of waves after passing through apertures, resulting in an energy distribution in the geometric shadow region.

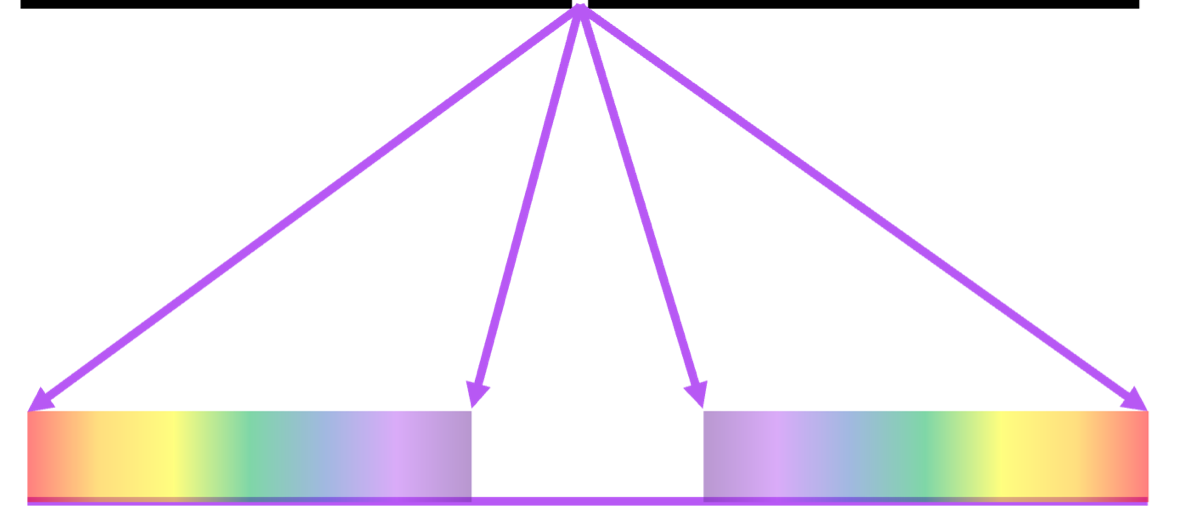

Single-slit diffraction of a monochromatic source results in the constructive and destructive interference of out of phase waves, called Huygens’ principle. A single-slit diffraction pattern contains a central maximum intensity followed by minima and maxima of decreasing amplitude and intensity, as shown below:

To calculate the angle of the first minimum (θ), based on slit width (b) and wavelength (λ), use the formula:

sinθ=bλ

If the angle is less than 12.5°, small angle approximation can be used, changing the formula to:

θ=bλ

The relative intensities and amplitudes of the first few maxima are outlined in the table below:

| Maximum | Central | 1st maximum | 2nd maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | Amax | 1/3rd Amax | 1/5th Amax |

| Intensity | Imax | 1/9th Imax | 1/25th Imax |

Effect of white light

If white light is involved in single-slit diffraction, different wavelengths diffract by different amounts. More specifically, white light forms the central maximum, followed by lower wavelengths having a lower angle of diffraction, and higher wavelengths having a higher angle of diffraction. This results in the distribution shown below:

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C4: Standing waves & resonance

Standing waves

Now that you understand the properties and phenomena of waves, it is important to learn about a second type of wave: the standing wave.

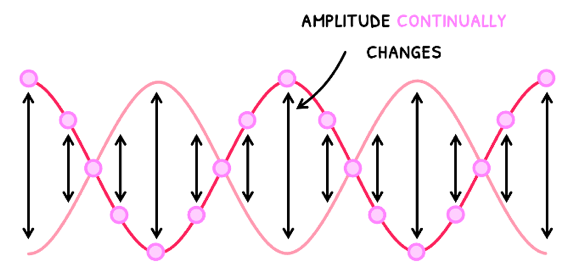

Standing waves are waves whose particles travel in a constant spatial pattern whilst their amplitude continually changes.

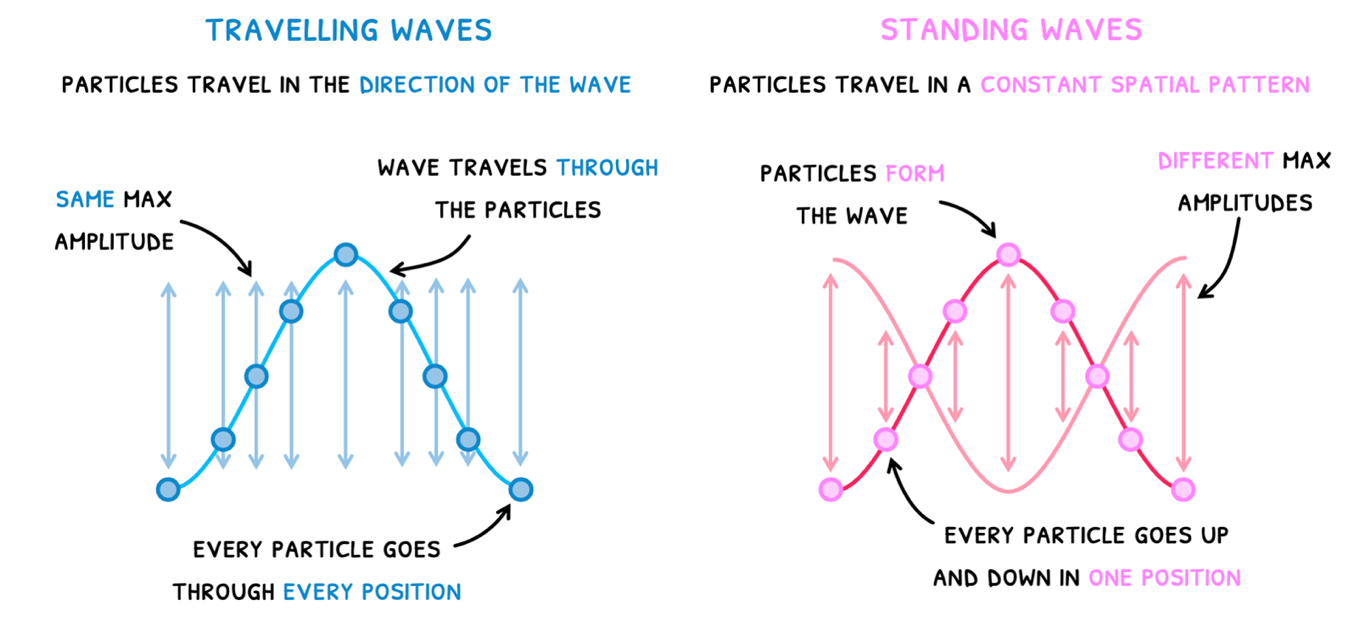

This may be difficult to visualize, so let’s compare this to a travelling wave.

- In a travelling wave, the wave travels through the particles. Thus, every particle goes through every position in the wave, meaning all particles have the same maximum amplitude.

- In a standing wave, the particle forms the wave. Thus, every particle only goes through the up and down position of the wave in one location, meaning all particles have different maximum amplitudes.

This has two knock-on effects:

- In a travelling wave, energy will be propagated by the wave, but in a standing wave energy will not be propagated by the wave.

- In a travelling wave, all particles will have different phases, whereas in a standing wave all particles will have the same phase.

The reason it comes at the end of this topic is because you need to know about reflection before covering standing waves.

Standing wave are formed when two waves of the same amplitude and frequency move in opposite directions. This typically happens when an emitted wave reflects and meets itself again.

A common scenario where this occurs is during plucking of strings in an instrument. Because the strings are fixed at both ends, they vibrate as a wave in a cyclical pattern with a particular frequency. This means they exhibit simple harmonic motion.

Harmonics

A harmonic is simply a frequency at which simple harmonic motion is exhibited. Since musical instruments possess many notes, it means standing waves possess many harmonics.

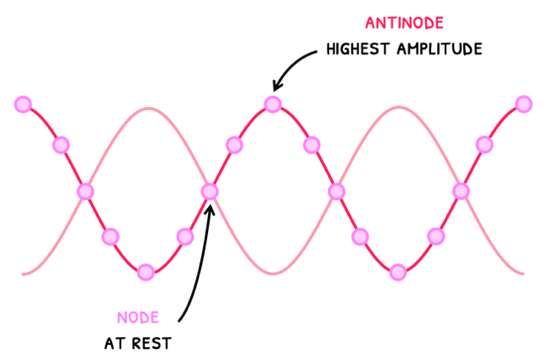

Each harmonic has a specific spatial pattern with some particles of the wave being at rest, called nodes (N), and other particles moving in a pattern. The particles moving in a pattern with the highest amplitude are termed antinodes (A).

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C5: Doppler effect

The Doppler effect

In C.5, the primary focus is the Doppler effect. This is the change in frequency of a wave incident on an observer due to the movement of a source or observer. You are expected to understand the Doppler effect for both sound waves and light waves.

Sound waves

For sound waves, two scenarios can occur. First, a sound source moves towards or away from a stationary observer.

- At position A: As the source moves, a wave is emitted. Since the source is moving, the second wave starts further from the first wave. This decreases the frequency of the wave that A will observe.

- At position B: As the source moves, a wave is emitted. Since the source is moving, the second wave starts closer to the first wave. This increases the frequency of the wave that B will observe.

Second, an observer moves towards or away from a stationary sound source.

- At position A: As A moves, a wave is emitted. Since A is moving closer, the second wave is received earlier. This increases the frequency of the wave that A will observe, and the formula for this is:

- At position B: As B moves, a wave is emitted. Since B is moving further, the second wave is received later. This decreases the frequency of the wave that A will observe, and the formula for this is:

Light waves

However, these formulas only work with sound waves due to their low velocities that can be measured. With light, the change in frequency (Δf) and wavelength (Δλ) due to a moving source or observer are related:

fΔf=λΔλ

When an observer or source is moving away and the frequency of light decreases, it is called a red shift. When an observer or source is moving closer and the frequency of light increases, it is called a blue shift.

Sail through the IB!

C5: Further Doppler effects (HL)

The Doppler effect

In the HL syllabus, you are expected to quantify the observed frequency for sounds waves and mechanical waves. For this, the previous explanation are reviewed.

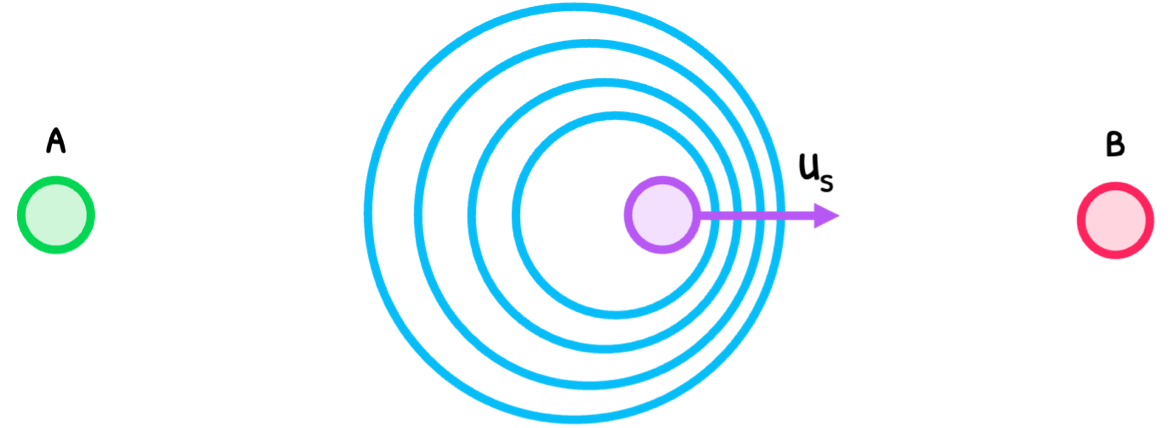

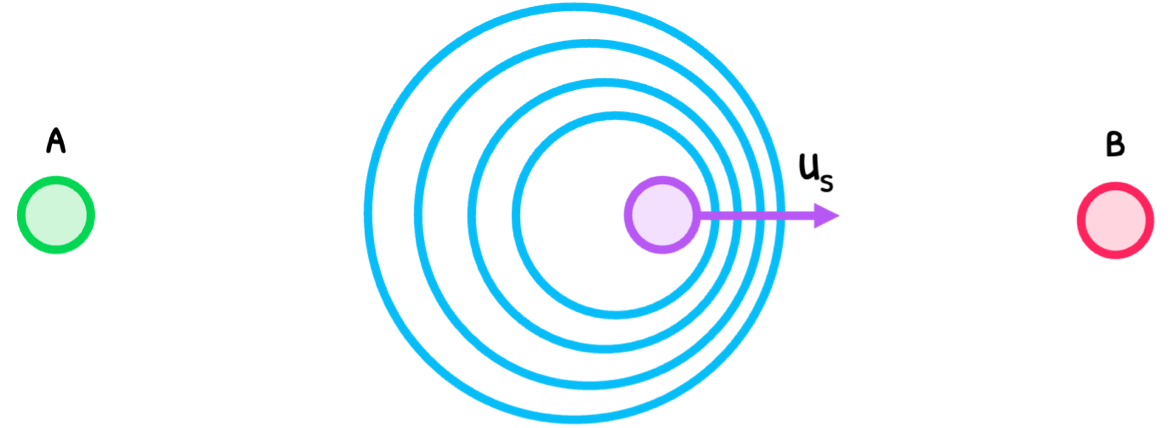

First, imagine a source moving with speed (us) and emitting a sound wave of frequency (f) and speed (v), as shown below:

At position A: As the source moves, a wave is emitted. Since the source is moving, the second wave starts further from the first wave. This decreases the frequency of the wave that A will observe, and the formula for this is:

f′=fv+usv

At position B: As the source moves, a wave is emitted. Since the source is moving, the second wave starts closer to the first wave. This increases the frequency of the wave thatBA will observe. The formula for this is:

f′=fv−usv

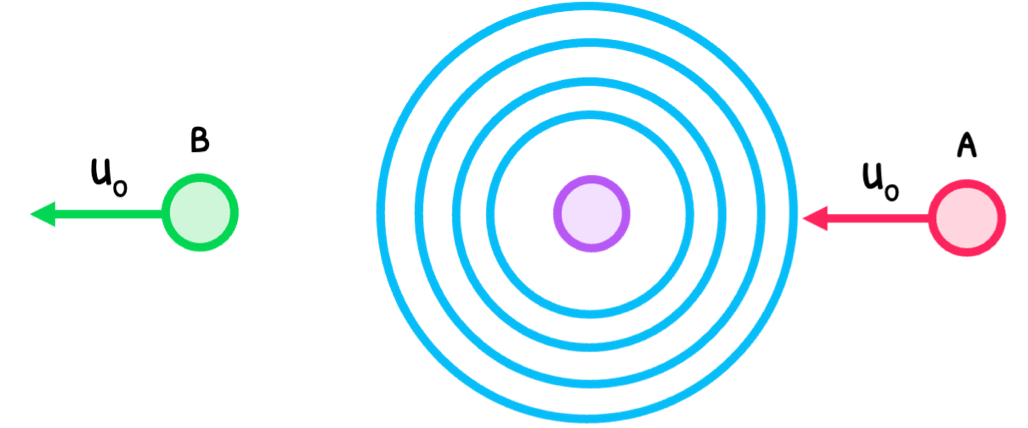

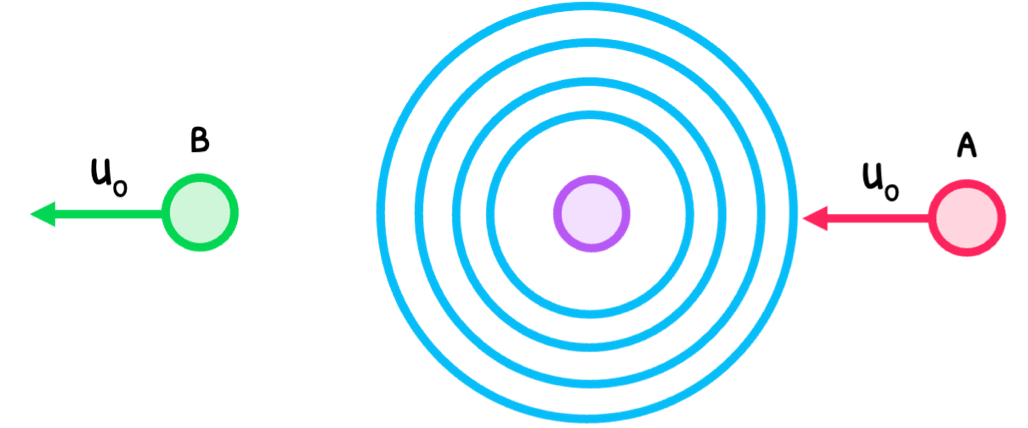

Second, imagine a source emitting a sound wave of frequency f and speed v, an observer A moving towards it with speed uo, and an observer B moving away with speed uo, as shown below:

At position A: As A moves, a wave is emitted. Since A is moving closer, the second wave is received earlier. This increases the frequency of the wave that A will observe, and the formula for this is:

f′=fvv+uo

At position B: As B moves, a wave is emitted. Since B is moving further, the second wave is received later. This decreases the frequency of the wave that A will observe, and the formula for this is:

f′=fvv−uo